Introduction

Rust, known for its emphasis on memory safety and performance, offers developers a powerful feature called “enums” that can greatly enhance the robustness and reliability of their code. Among the various kinds of enums available in Rust, two stand out as essential tools in handling common programming scenarios: Option and Result. We will explore Rust’s Option and Result enums, understanding their purpose, syntax, and how they enable developers to write safer and more reliable code.

Enums

Syntax Definition

You can specify an enum with a keyword enum, the name of the enum in capital camel-case, and the names of the variants in a block.

enum Size { Small, Medium, Large, ExtraLarge,}You can stop there if you want, and just use it like that, in which case it is sort of like an enum in C. Just namespace into the enum and away you go.

let my_size = Size::Small;Data Associated with Variants

However the real power of a Rust enum comes from associating data and methods with the variants. You can always have a named variant with no data. A variant can have a single type of data, a tuple of data, or an anonymous struct of data.

enum Size { Small, // no data Medium, Large, ExtraLarge, CustomLarge(String, u32), // tuple CustomMedium(u32), // single type MoreCustom { width: u32, height: u32 }, // anonymous struct}An enum is sort of like a union in C only so much better. If you create an enum the value can be any one of these variants.

For example: your Size could be Small with no data associated with it. Or it could be an CustomMedium with a single byte in it, or it could be a CustomLarge with a String and a unsigned 32-bit integer in it. Or it could be a MoreCustom with an anonymous struct with a width and a height in it.

enum Size { Small, Medium, Large, ExtraLarge, CustomLarge(String, u32), // tuple CustomMedium(u32), // single type MoreCustom { width: u32, height: u32 }, // anonymous struct}

use Size::*;let first_size = CustomLarge(String::from("hello"), 32);let second_size = CustomMedium(32);let third_size = MoreCustom { width: 32, height: 32 };Generics

Even better, you can implement functions and methods for an enum. You can also use in enums with generics.

Option is a generic enum in the standard library that you will use all the time.

enum Option<T> { Some<T>, None,}The T in angle brackets means any type. You don’t have to use T, you could use some other valid identifier, but the idiomatic thing to do in Rust is to use T or some other capital letter.

The Option enum represents when something is either absent or present. If you’re trying to reach for a null or nil value like in other languages, you probably want to use an Option in Rust. You either have some value wrapped in the Some variant, or you have None.

Because enums can represent all sorts of data, you need to use patterns to examine them. If you want to check for a single variant, you use the “if let” expression. “if let” takes a pattern that will match one of the variants.

if let Some(x) = my_var { println!("x is {}", x);}If the pattern does match, then the condition is true and the variables inside the pattern are created for the scope of the “if let” block. If the pattern doesn’t match then the condition is false.

Pattern Matching

This is pretty handy if you care about one variant matching or not, but not as great if you need to handle all the variants at once. In that case, you use the match expression, which is match, a variable whose type supports matching, like an enum.

match my_var = { Some(x) => { println!("x is {}", x); }, None => { println!("no value"); },}The body of the match in braces, where you specify patterns followed by double arrows, which are equal signs followed by greater than symbols pointing to an expression that represents the return value of that arm of the match.

Match expressions require you to write a branch arm for every possible outcome. In other words, the patterns in a match expression must be exhaustive. A single underscore all by itself is a pattern that matches anything and can be used for a default or anything-else branch.

match my_var = { _ => { println!("I don't care what it is"); },}Note that even though you will often see blocks as the expression for a branch arm, any expression will do, including things like function calls and bare values.

let x = match my_var = { Some(x) => x.multiplied() + 1, None => 15,}Either all branch arms need to return nothing or all branch arms need to return the same type.

Remember that if you actually use the return value of an expression that ends in a curly brace like match, if let, or if, or a nested block, then you have to put a semicolon after the closing brace. If you don’t use the return value of a braced expression then Rust lets you cheat and leave off the semicolon.

Handle null value with Option

First, let’s look a little more at Option. Here’s the definition of Option again.

enum Option<T> { Some<T>, None,}As I said earlier, Option is used whenever something might be absent.

Here is how you could create a None variant of an Option.

let mut x: Option<i32> = None;I specified the type that Some will wrap in angle brackets after the Option. Notice that I don’t have a use statement bringing into scope option or its variants Some or None from the standard library. Since Option and its variants are used so much they’re already included in the standard prelude, which is the list of items from the standard library that are always brought into scope by default.

If you ever use Option with a concrete type, then the compiler will infer the type, which means you can leave the type annotation off of the declaration most of the time.

let mut x: Option<i32> = None;x = Some(5)is_some and is_none

There’s a handy helper method called is_some() that returns true if x is the Some variant. There is also an is_none() method that does just the opposite.

let mut x: Option<i32> = None;x = Some(5)x.is_some(5) // truex.is_none(6) // falseOption implements the IntoIterator trait, so you can also treat it similar to a vector of 0 or 1 items and put it in a for loop.

let mut x: Option<i32> = None;x = Some(5)x.is_some(5) // truex.is_none(6) // false

for i in x { println!("{}", i); // prints 5}You ought to read through the methods for Option, because you will end up using them a lot.

Handle error with Result

The other important enum is Result. Result is used whenever something might have a useful result, or might have an error. This turns up especially often in the io module.

Here is the definition of the Result enum.

#[must_use]enum Result<T, E> { Ok(T), Err(E),}First, you’ll see that the type wrapped by Ok and the type wrapped by Err are both generic but independent of each other. Second, the #[must_use] annotation makes it a compiler warning to silently drop a result. You have to do something with it.

Rust strongly encourages you to look at all possible errors and make a conscious choice what to do with each one. Anytime you deal with i/o failure is a possibility, so Results are used a lot there like I said earlier.

Let’s see it in action!

use std::fs::File;

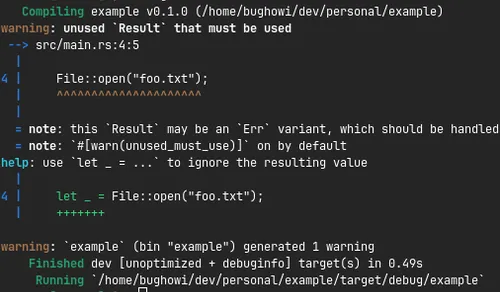

fn main() { File::open("foo.txt");}Here I bring std::fs::File into scope and then try to open a file. This returns a Result because the file might not get opened successfully. Since I dropped the Result without doing anything with it, I get this compiler warning: “unused std::result::Result that must be used”.

The point is: ignoring errors is not a safe thing to do! So let’s go choose something to do with our Result.

Unwrap

The simplest thing you could choose to do is to unwrap the Result with the unwrap() method.

use std::fs::File;

fn main() { let res = File::open("foo.txt"); let f = res.unwrap();}If the Result is an Ok then this gives you the File struct that you wanted. If the Result is an Err then this crashes the program. In some cases crashing the program may be what you want. In any case, you get to choose.

Expect

Another option is the expect() method.

use std::fs::File;

fn main() { let res = File::open("foo.txt"); let f = res.except("error message");}It’s exactly the same as unwrap(), except that the string that you pass to expect() is also printed in the crash output, so you can provide yourself a little bit of custom context as to why the crash occurred.

is_ok and is_err

Just like Option, there are helper methods like is_ok() and is_err() that return booleans.

use std::fs::File;

fn main() { let res = File::open("foo.txt"); if res.is_ok() { let f = res.unwrap(); }}Here we know that unwrap() will never crash because we’ve made sure it was an Ok already.

Pattern matching

Of course, you can always do full pattern matching as well.

use std::fs::File;

fn main() { let res = File::open("foo.txt"); match res { Ok(f) => { /* do something with the File */ } Err(e) => { /* handle the error */ } }}Here I match on a Result and execute different blocks depending on what I got back.

Conclusion

That’s it for enums! You’ve seen how to use them to handle null values and errors. You’ve also seen how to use them to create your own types. Hopefully you can see how powerful they are. They’re used all over the place in Rust, so you’ll be seeing them a lot.