As a beginner diving into Rust programming, understanding the concepts of borrowing and ownership is crucial for writing safer and more efficient code. Unlike many other programming languages, Rust’s memory management system enforces strict rules that eliminate common bugs such as null pointer dereferences, data races, and memory leaks. In this post, we will explore the core principles of borrowing and ownership in Rust and unravel the underlying mechanisms that make it a robust and reliable language for system-level programming.

Ownership

Ownership is what makes those crazy safety guarantees possible and makes Rust so different from other systems programming languages. Ownership is what makes all those informative compiler error messages possible and necessary.

Ownership Rule’s

There are three rules to ownership:

1. Each value has an owner.

First, each value has an owner. There is no value in memory that doesn’t have a variable that owns it.

2. Only one owner

There is only one owner of a value. No variables may share ownership. Other variables may borrow the value which we’ll talk about, but only one variable owns it.

3. Value gets dropped if its owner goes out of scope

Third, when the owner goes out of scope, the value gets dropped immediately.

Let’s see ownership in action.

Let’s create a string s1 and then create another variable s2 and assign s1 value to it.

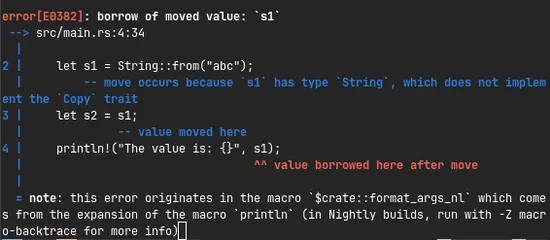

fn main() { let s1 = String::from("abc"); let s2 = s1; println!("The value is: {}", s1);}What happens to this string is not a copy. At this point the value for s1 is moved to s2 because only one variable can own the value. If we try to go ahead and use s1 after this point, we get a compiler error: borrow of moved value s1.

So what’s going on here?

In the code above, it is evident that we are moving the value of s1 to s2. The concept of moving implies the transfer of ownership from one variable to another. In the given example, we transfer ownership from s1 to s2, which means that s2 now owns the value, and the compiler considers s1 uninitialized. Consequently, attempting to use s1 after the move would result in a compilation error.

What if we didn’t want to move the value but copy it instead? To make a copy of s1 we would call the clone() method.

fn main() { let s1 = String::from("abc"); let s2 = s1.clone(); println!("The value is: {}", s1);}Both the move and the clone situations, the three rules of ownership are satisfied: 1) the values have owners, and 2) only one owner, and 3) when the variables go out of scope the values will be immediately dropped.

Borrowing

Another move situation: Let’s start with the same string and make a function that takes a string and returns nothing.

fn main() { let s1 = String::from("abc"); do_something(s1);}

fn do_something(s: String) { // do something}If we pass s1 to that function, s1 is moved into the local variable s in do_something(), which means we can’t use s1 anymore because it got moved!

So what do we do?

One option is to move it back when we’re done. We’ll just make s1 mutable, add a return type to do_something(), and then return s as the tail expression, which gets moved back out of the function and used to reinitialize s1.

fn main() { let mut s1 = String::from("abc"); s1 = do_something(s1); println!("{}", s1);}

fn do_something(s: String) -> String { s}But that’s usually not the pattern that you want! Passing ownership of a value to a function usually means a function is going to consume the passed in value. For most other cases, you should use references, which is why it’s time to talk about references and borrowing.

Mutable and Immutable references

Instead of moving our variable, let’s use a reference.

fn main() { let s1 = String::from("abc"); do_something(&s1); println!("{}", s1);}

fn do_something(s: &String) { // do something}Here’s our do_something() function again, only this time it takes a reference to a string. The ampersand before that type indicates a reference to a type. When we call do_something() we pass it a reference to s1, and s1 retains ownership of the value. do_something() borrows a reference to the value. The reference (not the value) gets moved into the function. At the end of the function the reference goes out of scope, and the reference gets dropped, so our borrowing ends at that point. After the function call, we can use s1 like normal, because the value never moved.

Under the hood, when we create a reference to s1, Rust creates a pointer to s1, but you will almost never talk about pointers in Rust because the language automatically handles their creation and destruction for the most part, and makes sure they’re always valid using a concept called lifetimes. Lifetimes can be summed up as a rule that references must always be valid, which means the compiler won’t let you create a reference to outlives the data it is ultimately referencing, and you can never point to null.

References default to immutable, even if the value being referenced is mutable.

fn main() { let mut s1 = String::from("abc"); do_something(&s1);}

fn do_something(s: &String) { s.insert_str(0, "Hi, "); // Error}But if we make a mutable reference to a mutable value then we can use the reference to change the value as well.

fn main() { let mut s1 = String::from("abc"); do_something(&mut s1);}

fn do_something(s: &mut String) { s.insert_str(0, "Hi, ");}The syntax for a mutable reference is a little special: ampersand *, mut, space, variable or type.

Now wait, why didn’t we have to dereference the mutable reference in order to alter s in the do_stuff() method?

fn main() { let mut s1 = String::from("abc"); do_something(&mut s1);}

fn do_something(s: &mut String) { s.insert_str(0, "Hi, ");}Look at this, we are using the same dot syntax to access a string method on a mutable reference as we do for the value itself. How does that work?

The dot operator for a method or a field auto-dereferences down to the actual value. So at least when you’re dealing with the dot operator you don’t have to worry about whether something is a value or a reference or even a reference of a reference.

If we manually dereferenced s, it would look like this:

fn main() { let mut s1 = String::from("abc"); do_something(&mut s1);}

fn do_something(s: &mut String) { (*s).insert_str(0, "Hi, ");}You use an asterisk immediately before a reference to dereference to the value, similar to C. The dereference operator has pretty low precedence, so you’ll sometimes need to use parentheses.

With most other operators (like the assignment operator for example) you’ll need to manually dereference your reference if you want to read from or write to the actual value.

fn main() { let mut s1 = String::from("abc"); do_something(&mut s1);}

fn do_something(s: &mut String) { (*s).insert_str(0, "Hi, "); *s = String::from("Replacement");}Here I’m dereferencing s so that I can replace the entire value.

Let’s stop and go over what references look like again. If you have the variable x, then :

&x-> Create an immutable reference to that variable value&mut x-> Create a mutable reference to a that variable value

Similarly with types, if i32 is the type of your value, then:

&i32-> This is the type of your immutable reference&mut i32-> This is the type of your mutable reference

Going the other way around, if your variable is a mutable reference to a value.

x: &mut i32*x // a mutable i32Then dereferencing x gives you mutable access to the value.

And if x is an immutable reference to a value,

x: &i32*x // a immutable i32then dereferencing x gives you immutable access to the value.

Borrowing Rules

Naturally, since references are implemented via pointers, Rust has a special rule to keep us safe. At any given time you can have either exactly one mutable reference or any number of immutable references.

This rule applies across all threads. When you consider that references to a variable may exist in different threads, it starts to make it pretty obvious why it’s not safe to have multiple mutable references to the same variable at the same time without some type of locking. But if all the references are immutable then there’s no problem. So you can have lots of immutable references spread across multiple threads.

All these rules I’ve been talking about are enforced by the compiler, and by enforced I mean compiler errors, lots of compiler errors! At first you’re like Aaargh! I hate the compiler! It keeps giving me errors! But then as you get the hang of it you realize you don’t get mysterious segfaults anymore, and the error messages are really pretty informative! And if the code compiles, it works! And that is an amazing feeling!

Conclusion

Understanding Rust’s borrowing and ownership concepts is crucial for writing safe and efficient code. By grasping the principles of ownership transfers and borrowing, you can effectively manage memory, eliminate common bugs, and harness the full potential of Rust’s powerful memory management system. Whether you’re a beginner or an experienced developer, mastering these concepts will empower you to build robust and reliable software. So, dive into Rust’s borrowing and ownership, and embark on a journey towards safer and more efficient programming.